Nudging in choice architecture

People do not always act rationally in ways that promote their health or a sustainable lifestyle. Knowledge about healthy lifestyles and environmental issues is only one factor influencing motivation, alongside beliefs, values, emotions, and social factors.

A nudge is a change in choice architecture, the environment where people make decisions. This change aims to make a particular choice easier while maintaining the freedom to choose otherwise.

Nudging was introduced in the highly acclaimed 2008 book “Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness” by Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein. Afterward, behavioral science, and nudging in particular, have attracted a lot of attention (Halpern, 2015; OECD, 2010).

Nudges are often cost-effective, quick to implement, and easily scalable to large populations. For example, nudges can aim to promote health and reduce emissions by encouraging people to choose public transportation or bicycles over cars for commuting.

Although nudging is an attractive and usually a well-accepted way to steer people’s behavior, the impact of nudges on behavior is often small and can fade quickly. Their potential lies in the possibilities of scaling-up small and easy interventions, where their cumulative effects generate a significant systemic impact. It is important to emphasize that nudges are not meant to replace other behavioral steering methods–such as infrastructure changes, financial incentives, or policy decisions–but rather to complement them.

Design, implementation, and evaluation of intervention

Several practical context-specific or generic frameworks are developed to assist scientists, practitioners, and policymakers in designing and evaluating the intervention. We present a six-step guide for choice architecture interventions highlighting the important tasks involved in the process (Tuominen & Koi, in progress). Working through these steps can help to optimize the effectiveness of the intervention.

- Define the problem: What is the intervention aiming to achieve? It is important to translate the problem into concrete behavior. What kind of behavior do you want to change, and what do you want people to do instead? Who is the target group? Understanding and defining the problem also includes assessing the target group’s needs.

- Understand the choice architecture: Once the problem and the target group have been defined, understand the target group’s operational environment and decision-making situations. At this stage, information is gathered from various sources, such as surveys, observations, and interviews with the target group, workshops, and by utilizing previous literature and data. What are the critical decision points related to the target behavior? What factors influence behavior at each decision point? What are the barriers and drivers (social, physical, psychological) of behavior? How to operationalize?

- Develop the intervention options: During the development phase of interventions, it is advisable to use a theory-based framework as a tool. In the next section, we will introduce one such tool, the FEAST framework. Other useful and widely used tools include, for example, the COM-B Model (Capabilities, Opportunities, Motivation) (Michie et al., 2011). Whenever an intervention is implemented, there is an underlying understanding of how and why a particular measure affects behavior. Theory helps the intervention designer consider key factors influencing behavior and the means of influencing it. The goal is to target factors that strongly connect to the behavior in question, which are, on average, low in the target group and can be modified. A good starting point is to consider whether the choice is rare or routine. In the previous phase, barriers were identified. Now, a hierarchy can be formed from them. Which of the barriers is the most significant for the action from the perspective of the individual and previous research? Once intervention options have been developed, ethical challenges and related questions are examined. At the same time, it can be considered whether nudges should be chained or implemented as part of other measures.

- Pilot the intervention: At the piloting stage, ensuring that the intervention is affordable, easily implementable in practice, and considered meaningful and acceptable by both the target group and the implementers (Abraham & Denford, 2020). High intervention fidelity is critical from the perspective of the intervention’s effectiveness (e.g., Eldridge et al., 2016). Intervention fidelity can also be strengthened by involving members of the target group and the implementers in the design of the intervention (Abraham & Denford, 2020). This can be called the co-creation process. Other issues to be investigated include the recruitment rate, the dropout rate among participants, and whether the evaluation instruments (e.g., behavior measurement) are acceptable, feasible, and reliable. Is it possible to implement a blinding design?

- Evaluate: A broader evaluation aims to ensure that resources are not spent on implementing and executing interventions whose effectiveness is likely improbable. Is it possible for the intervention to achieve the desired effects? A randomized controlled trial (RCT) is generally considered the standard evaluation design. In an RCT design, members of the target group are randomly assigned to either the intervention or control group. The intervention is implemented only in the intervention group, while the control group continues as before. Follow-up can determine how the target behavior has changed. Pre-post measurements can also investigate effectiveness (Craig et al., 2008). It is also helpful to examine the internal processes of the intervention, i.e., by what mechanisms, on whom, and under what conditions the intervention works or does not work.

- Scale up the interventions: Once the intervention has been evaluated and repeatedly proven effective, it is justified to begin disseminating and implementing it in new contexts and scaling up to target new groups or populations (Abraham & Denford, 2020). At this stage, it is also important to have a careful and comprehensive implementation planning and evaluation process and collaborate with the staff of the operational environments targeted by the intervention.

How to encourage behavior change?

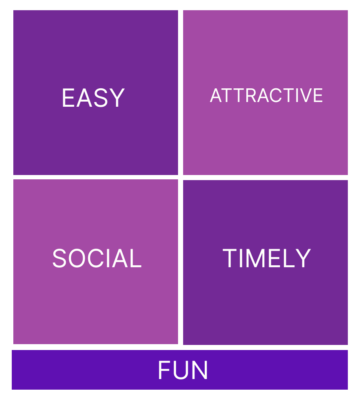

To encourage a behavior, one should make it Easy, Attractive, Social, and Timely (EAST) (Behavioural Insights Team, 2014). The EAST framework has been developed by the Behavioural Insights Team and it has proven a helpful tool for policymakers all over the world. Sunstein (2020), however, thought that the model was missing something essential and added one new element: Fun.

Addition of an element of enjoyment has been supported by research: for example, two methods to increase vegetable consumption, one with labels highlighting health benefits and another emphasizing enjoyment and taste, were tested at the Stanford University (Turnwald et al., 2019). Both methods were effective, but the enjoyment-focused labels proved more powerful, with an excellent 29% increase in vegetable consumption compared with 14% increase – still a good result – with health-focused labels.

There is a large body of evidence on what influences behavior. Although not attempting to be an exhaustive list, the EAST – or FEAST – framework can help policymakers and practitioners consider effective behavioral approaches. The definitions for the five principles are (The Behavioural Insights Team, 2014):

- Make it Easy: Use default settings to simplify choices, reduce effort required to act, and simplify messages to increase response rates.

- Make it Attractive: Draw attention with images, color, or personalization. Use effective rewards and sanctions, like financial incentives or lotteries.

- Make it Social: Highlight common behaviors to encourage others, leverage social networks for support, and encourage commitments to others.

- Make it Timely: Prompt actions when people are most receptive, especially during life changes. Focus on immediate costs and benefits, and help people plan their responses to barriers.

- Make it fun: Human beings need fun in their lives. Emphasize enjoyment and produce a sense of optimism, unity, hope, and smiles instead of despair, anger, division, and fear.

How to nudge ethically?

Some nudges are ethically better than others. Ethical considerations can be acknowledged best by incorporating them to all stages of nudge development (see Tuominen & Koi model above). Taking that one is nudging for a good choice, ethics of nudging consists of balancing and fitting together various factors. Each factor has some moral weight in decision-making but none of them alone deems the nudge to be ethically bad or good. The central factors include:

- Transparency: Can targets notice that nudging is taking place? Can they understand the goals behind the nudge?

- Justice and fairness: Do the nudge have desirable or undesirable redistributive outcomes?

- Beneficence: If the nudge self-regarding or other-regarding? If it is other-regarding, how are the possible costs to the targets justified?

- Social acceptability: Do the targets and other stakeholders accept the goal of the nudge and the way of influencing their choice?

- Delegation: Does the nudger have the right to nudge the targets?

- Goal: Are the targets nudged for the best choice or to a choice that is just a bit better than their current choice? Can the best choice be known? Is the best choice feasible?

- Side-effects: Does the nudge have unwanted side-effects?

- Autonomy: Does the nudge infantilize, undermine agency or strengthen conscious deliberation? Is it manipulative or trickery?

What does scientific research tell us about public transportation nudges?

Scientific research reveals some patterns regarding effectiveness of nudges in promoting public transportation. Targeted information campaigns, financial incentives, and personalized travel plans have shown the most promise in shifting behaviors toward increased public transport use. In contrast, nudges relying on social norm messaging, weak default mechanisms, and gamification without financial incentives have not been able to generate significant behavior change.

Challenges in implementing nudging strategies include poor public transport service quality, which limits behavior change potential, and the unreliability of self-reported behavior changes, suggesting an attitude-behavior gap. While personalization of interventions has shown promise, it remains difficult to scale effectively in large-scale public transportation initiatives. However, use of Artificial Intelligence may provide solutions for personalization of nudges. Thus, nudges alone often fall short of achieving long-term changes in travel habits. Below is a more detailed description of the literature.

Information campaigns with or without financial incentive

A randomized controlled study indicated that the combination of an information campaign (emails about employer’s new public transportation benefits) and a small monetary incentive (for reducing their frequency of parking) influenced awareness, attitudes, and hypothetical intentions to reduce driving to work, but did not translate into action (Rosenfield et al. 2020). Participants reported an intent to reduce car use, but complained about the poor quality of transit service. Thus, such system-level challenges may explain why the participants could not bridge the attention-behavior gap.

Another information campaign found no effect with email messages highlighting loss aversion, i.e. drawing attention to money lost when the participants had not taken advantage of previously offered free bus journeys (Kristal & Willans, 2020). In reality, however, the public transportation commute options may have been less attractive for the participants of that study, who worked at an airport outside a large city.

Personalized travel plans

Personalized travel plans were delivered to university students through a mobile application and email, and resulted in an 8% shift from private car use to public transport in Rome (Italy), based on longitudinal GPS data (Sottile et al. 2021). Based on self-report, active mobility became more frequent, car sharing increased, attitudes towards car use became less positive, and awareness of CO2 emissions was increased. However, social norms were not affected during a 2-week intervention, which can indeed be argued to be too short period for social norms to change. The personalized travel plans included suggestions for sustainable travel alternatives, detailed environmental effects of the travel choice, personalized slogans, and information on sustainable mobility.

Social norm messaging with or without financial incentive

In nudge literature, social norm nudges and defaults have effectively promoted sustainable behavior in water conservation (Brent et al., 2015) and waste reduction (Kallbekken, & Sælen, 2013). However, their effectiveness in transportation is still unclear.

Private car use was attempted to be reduced by encouraging public transport subscriptions through social norm and default nudges, but failed to show their effectiveness (Hauslbauer et al., 2022). In the social norm nudge, participants received information emphasizing that a significant portion of their peers or colleagues had already subscribed to the public transport ticket, leveraging social influence to encourage subscription. In the default nudge, participants were presented with a pre-selected option to subscribe to a public transport ticket. Reasons for not being effective likely include the non-routine nature of successful nudges, resistance due to monetary costs, and the perceived flexibility and spontaneity of car use. The default nudge may have been too soft, and the effort to opt out was minimal, making it easy for participants to decide against the ticket. Thus, stronger default nudges may be required to make opting out of undesired behaviors more difficult.

A large-scale natural experiment with over 14,000 participants concluded that social norm nudges might not be the most promising approach while there is scope for long-term behavior change (Gravert et al., 2021). The study investigated whether social norms can positively affect public transport usage compared to traditional price instruments and whether behavior change persists after removing nudges and incentives. The participants were given one of three offers: 1) a two-week free travel card, 2) a two-week free travel card combined with social norm nudge (comparison with the neighbors’ public transport use), and 3) a four-week free travel card. Descriptive social norms did not have an effect, but the doubled economic incentive significantly increased uptake and long-term usage, and the increase persisted for months after the incentive was removed. Successful social norm nudges might thus require more detailed knowledge about the population and personalization.

Gamification with or without financial incentive

At least three studies have investigated gamification in promoting public transportation, but none of them found gamification alone to be effective. A study delivering free bus cards, encouraging messages, and personalized feedback found that the key to behavior change was a combination of a financial reward (free bus card) with nudging by encouraging messages and personalized feedback, not social reward, gaming, or framing with health benefits of sustainable traveling (Lieberoth et al., 2018).

Another study used personalization and persuasive techniques via mobile application, but failed to bring about any behavioral change, measured objectively with GPS route logs (Bothos et al., 2014). The application was designed to help find and utilize low-emission travel options and included different persuasive strategies; for example, it suggested green default route options and displayed environmentally friendly options in a more prominent position in the interface. According to the self-report, the application increased environmental awareness, and self-reported behavior change towards more environmentally friendly travel modes. Thus, this study also supports the existence of the attitude-behavior gap, indicating that people’s behavior does not necessarily align with their attitudes.

Lessons to learn from previous nudge studies also point out the risk of high dropout due to, for example, inadequate communication with participants or too laborious study settings. No changes were found either in travel mode choice or attitudes toward the environment in a study developing and testing a mobile application (Gabrielli et al., 2014). The application included multimodal journey planning, rewards, goal setting, self-monitoring, and a feature to report disruptive events. The trials suffered from discouraging elements from high battery consumption of the automatic journey tracking to laborious travel diaries.

Is nudging a useful method for behavior change?

Despite the methodological challenges in studies and mixed evidence provided by the scientific research, nudging can still be recommended for policymakers, but with caveats and a strategic approach. Here are some advice:

- Policymakers have more flexibility than researchers, allowing them to test and refine nudges over time based on real-world feedback.

- The combination of nudging with other behavior steering methods is key: Nudging is low-cost and politically feasible, making it a useful complement to financial incentives, regulatory changes and infrastructure improvements.

- Nudging effectiveness is context-dependent; personalized and well-targeted nudges tend to perform better than generic ones.

- Ethical considerations matter, but well-designed nudges can align with public interest goals without restricting freedom of choice (e.g., making public transport information clearer, framing messages to encourage sustainable behavior). Effectiveness should be balanced with transparency and ethical considerations. For more information about ethical consideration of climate nudges, please read here (LINKKI).

Go back to Nudge Co-creation Playbook main page

Move to Nudges for Public transportation page

Literature list:

Abraham,C., & Denford, S. 2020 in Hagger, M. S., Cameron, L. D. (Linda D., Hamilton, K., Hankonen, N., & Lintunen, T. (2020). The handbook of behavior change. Cambridge University Press.

Boniface, S., Scantlebury, R., Watkins, S. J., & Mindell, J. S. (2015). Health implications of transport: Evidence of effects of transport on social interactions. Journal of Transport & Health, 2(3), 441–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jth.2015.05.005

Bothos, E., Prost, S., Schrammel, J., Röderer, K., & Mentzas, G. (2014). Watch your emissions: Persuasive strategies and choice architecture for sustainable decisions in urban mobility. PsychNology Journal, 12(3), 107–126.

Brent, D. A., Cook, J. H., & Olsen, S. (2015). Social comparisons, household water use, and participation in utility conservation programs: Evidence from three randomized trials. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 2(4), 597–627. https://doi.org/ 10.1086/683427

Buchanan, M. (2019). The benefits of public transport. Nat. Phys. 15, 876. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41567-019-0656-8

Clavien, C. (2018). Ethics of nudges: A general framework with a focus on shared preference justifications. Journal of Moral Education 47(3), 366-382. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2017.1408577

Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2008). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: the new Medical Research Council guidance. BMJ, 337(7676), 979–983. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

Currie, G., & Stanley, J. (2008). Investigating Links between Social Capital and Public Transport. Transport Reviews, 28(4), 529–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/01441640701817197

Dolan, P., Hallsworth, M., Halpern, D., King, D. & Vlaev, I. (2010). Mindspace: influencing behavior for public policy. Institute of Government, London, UK.

Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., Bond, C. M., & Lazzeri, C. (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: Development of a conceptual framework. PloS One, 11(3), e0150205–e0150205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

European Commission: Directorate-General for Mobility and Transport. (2024). Transport in the European Union: current trends and issues. Publications Office of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2832/131741.

European Environment Agency. (2024). Transport and mobility.

Epley, N., & Schroeder, J. (2014). Mistakenly seeking solitude. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(open in a new window), 1980–1999. doi: 10.1037/a0037323

Gabrielli, S., Forbes, P., Jylhä, A., Wells, S., Sirén, M., Hemminki, S., Nurmi, P., Maimone, R., Masthoff, J., & Jacucci, G. (2014). Design challenges in motivating change for sustainable urban mobility. Computers in Human Behavior, 41, 416–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.05.026

Gravert, C., & Olsson Collentine, L. (2021). When nudges aren’t enough: Norms, incentives and habit formation in public transport usage. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 190, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2021.07.012

Hauslbauer, A.L., Schade, J., Drexler, C.E. et al. Extending the theory of planned behavior to predict and nudge toward the subscription to a public transport ticket. Eur. Transp. Res. Rev. 14, 5 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12544-022-00528-3

Halpern, D. (2015). Inside the Nudge Unit: How Small Changes Can Make a Big Difference. New York: Random House.

Kallbekken, S., & Sælen, H. (2013). ‘Nudging’ hotel guests to reduce food waste as a win–win environmental measure. Economics Letters, 119(3), 325–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2013.03.019

The behavioral insights Team. (2024). EAST: Four simple ways to apply behavioral insights. London, UK.

Kristal, A. S., & Whillans, A. V. (2020). What we can learn from five naturalistic field experiments that failed to shift commuter behaviour. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(2), 169–176. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-019-0795-z

Lades, L. K. & Delaney, L. (2022). Nudge FORGOOD. Behavioural Public Policy 6(1), 75-94. https://doi.org/10.1017/bpp.2019.53

Lieberoth, A., Holm Jensen, N., & Bredahl, T. (2018). Selective psychological effects of nudging, gamification and rational information in converting commuters from cars to buses: A controlled field experiment. Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour, 55, 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.02.016

Michie, S., van Stralen, M. M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: a new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science : IS, 6(1), 42–42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42

OECD (2021), Transport Strategies for Net-Zero Systems by Design, OECD Publishing, Paris, https://doi.org/10.1787/0a20f779-en.

Patterson, R., Webb, E., Hone, T., Millett, C., & Laverty, A. A. (2019). Associations of Public Transportation Use With Cardiometabolic Health: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Epidemiology, 188(4), 785–795. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwz012

Rissel, C., Curac, N., Greenaway, M., & Bauman, A. (2012). Physical activity associated with public transport use-a review and modelling of potential benefits. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 9(7), 2454–2478. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph9072454

Rosenfield, A., Attanucci, J. P., & Zhao, J. (2020). A randomized controlled trial in travel demand management. Transportation, 47(4), 1907–1932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11116-019-10023-9

Siipi, H. & Koi, P. (2022). The Ethics of Climate Nudges: Central issues for Applying Choice Architecture Interventions to Climate Policy. European Journal of Risk Regulation 13, 218-235. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2021.49

Sottile, E., Giacchetti, T., Tuveri, G., Piras, F., Calli, D., Concas, V., Zamberlan, L., Meloni, I., & Carrese, S. (2021). An innovative GPS smartphone based strategy for university mobility management: A case study at the University of RomaTre, Italy. Research in Transportation Economics, 85(2), 100926. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2020.100926

Sunstein, C. R. (2020). Behavioral Science and Public Policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Thaler, R.H., Sunstein, C.R. (2009). Nudge: Improving Decisions About Health, Wealth, and Happiness. Penguin.

Turnwald, B. P., et al. (2019). Increasing Vegetable Intake by Emphasizing Tasty and Enjoyable Attributes: A Randomized Controlled Multisite Intervention for Taste-Focused Labeling. Psychological Science, 30(11), 1603–1615.

Webb, E., Netuveli, G., & Millett, C. (2012). Free bus passes, use of public transport and obesity among older people in England. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979), 66(2), 176–180. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2011.133165

Wener, R., Evans, G., & Boately, P. (2005). Commuting stress: Psychophysiological effects of a trip and spillover into the workplace. Transportation Research Record: Journal of the Transportation Research Board, 1924, 112–117.